This website uses marketing and tracking technologies. Opting out of this will opt you out of all cookies, except for those needed to run the website. Note that some products may not work as well without tracking cookies.

Opt Out of Cookies|

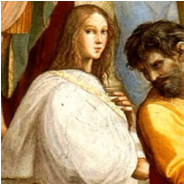

The Beautiful Lady in the Middle - Hypatia of Alexandria

by Olivia Pierson When Raphael painted his famous classical work, School of Athens, he rendered the form of a beseeching figure in white robes who was the only female in the fresco. She is also the only philosopher steadily gazing straight out of the work to make eye contact with the viewer. Her name is Hypatia of Alexandria (pronounced high-pay-shee-ah) and she was the victim of one of the most disgusting atrocities in human history. The story of how Hypatia came to be in Raphael’s work is a fascinating one. He was commissioned by the clergy to decorate the rooms of the Apostolic Palace in the Vatican. The fresco took him two years to complete, between 1509 and 1511. Raphael was required to show the patronising Bishop preliminary sketches of the fresco (a matter of painful frustration for any artist). Raphael had placed Hypatia to the very centre left in the foreground, beneath Plato and Aristotle, on the marble steps. Upon perusing the sketches, the Bishop asked, “Who is the beautiful lady in the middle?” Raphael replied, “She is Hypatia of Alexandria, the most famous studentof the School of Athens. She was a professor of philosophy, mathematics and astronomy at the University of Alexandria and certainly one of the greatest thinkers ever.” The Bishop at once commanded him to remove her. Hypatia was a Greek woman who lived and worked 1600 years ago in the great beating heart of the intellectual world, the famous Library of Alexandria, in Egypt. Under Roman rule, Alexandria was then part of the Eastern Empire governed from Constantinople, not Rome. The library itself was part of the museum (the Temple of the Muses) and the centre of the university. It had been built and patronized by the Ptolemaic dynasty, of which Cleopatra had been the last to rule. It was created in the third century BC in the time of Alexander the Great, and was totally destroyed seven centuries later; its destruction is still a disputed and tragic semi-mystery. Hypatia was a scientist, physicist, mathematician and astronomer, but her primary role was Head of the Neoplatonic School of Philosophy. This was a time when women were still considered to be mere property with little or no prospects, yet under the protection and guidance of her devoted father, Theon, the last head of the Museum of Alexandria, Hypatia was able to move freely and confidently about the city, teach science and philosophy to men, debate politics and the finer points of classical literature, whilst arrayed in the dignified robes of a scholar. Surviving accounts stand testimony to her natural beauty. Socrates Scholasticus, a fifth century historian wrote of her: “There was a woman at Alexandria named Hypatia, daughter of the philosopher Theon, who made such attainments in literature and science, as to far surpass all the philosophers of her own time. Having succeeded to the school of Plato and Plotinus, she explained the principles of philosophy to her auditors, many of whom came from a distance to receive her instructions. On account of the self-possession and ease of manner which she had acquired in consequence of the cultivation of her mind, she not infrequently appeared in public in the presence of the magistrates. Neither did she feel abashed in going to an assembly of men. For all men on account of her extraordinary dignity and virtue admired her the more.” Hypatia wasn’t just extraordinary because she was a female philosopher, she was known during her time to be the greatest philosopher of Alexandria. She taught Platonic and Aristotelian philosophy, she edited her father’s work on Euclidean geometry, she taught Pythagorean mathematics, and wrote her own works on astronomy and geometry – alas now lost to us. She invented certain scientific instruments: an astrolabe for measuring the positions of the sun, moon and planets, an apparatus for distilling water, and a graduated brass hydrometer for measuring the specific gravity of liquid. She believed that all boys and girls should be educated and that superstition was the greatest obstacle to true knowledge and learning. She once wrote: “Fables should be taught as fables, myths as myths, and miracles as poetic fancies. To teach superstitions as truth is one of the most terrible things. The mind of a child accepts them, and only through great pain, perhaps even tragedy can the child be relieved of them.” We have only fragments and small excerpts of Hypatia’s teachings, but it is obvious that she was no friend of religion. She wrote: “No priests should be allowed to force their beliefs on you and rob you of your right to evolve your own way of life.” And: “All formal dogmatic religions are fallacious and must never be accepted by self-respecting persons as final.” Her father had invested in her as would any father of the time invest in the future of a son. Hypatia’s influence and fame eclipsed that of her father, indeed eclipsed the fame of any man of her city. Her bearing was one of a confident and beautiful woman, secure in the ability of her mind and practical abilities. She did not want to marry and rejected many suitors, perhaps fearing that a traditional union would limit her freedom of movement and accomplishment. During her time, Christianity was evolving strongly into theocratic rule (often violent) and she found herself at the very epicentre of a clash between civilisation and barbarism. Barbarism won. She inspired hatred in Cyril the Archbishop, who sought to stamp out any “pagan” influence in politics and culture in Alexandria. This hatred was also the result of her abiding friendship with Cyril’s main enemy, Orestes, the Roman Prefect, who often sought Hypatia’s counsel in matters of political and philosophical importance. According to Damascius, the last head of the School of Athens, writing one hundred years after Hypatia’s death, this hatred was also borne of some jealousy: "Hypatia’s style was like this: she was not only well-versed in rhetoric and in dialectic, but she was as well wise in practical affairs and motivated by civic-mindedness. Thus she came to be widely and deeply trusted throughout the city, accorded welcome and addressed with honor. Furthermore, when an archon was elected to office, his first call was to her, just as was also the practice in Athens…Now the following event took place. Cyril the bishop of the opposite sect was passing Hypatia’s house and noticed a hubbub at the door, “a confusion of horses and of men,” some coming, others going and yet others standing and waiting. He asked what was the meaning of the gathering and why there was a commotion at the house. Then he heard from his attendants that they were there to greet the philosopher Hypatia and that this house was hers. This information gave his heart such a prick that he at once plotted her murder. In the year 415 AD, as Hypatia continued to lecture, invent and write, she was in her chariot on her way to the university when a fanatical mob of Christians and desert monks, called into the city by Cyril, assaulted her. They stripped her naked and dragged her through the city to a church where she was beaten and then flayed alive with razor-sharp oyster shells until her flesh had been torn from her body. They dismembered her then burned her mutilated corpse for all to see. Her works were burned with the remains of her body. Alexandria succumbed to Christian theocratic rule and the beginning of the Dark Ages ensued. Soon after her death, the Alexandrian Library, museum and university were obliterated. Henceforth the memory of Hypatia, her achievements and teachings were deemed to be an enemy of Christianity. In reality, she was the last, great, classical philosopher standing between an age of free intellectual inquiry and the looming shadows of dogmatic intellectual slavery. This descending darkness was to bind free thought in a mental prison for another 1300 years, until 18th Century Enlightenment thinking would again light a path to liberty. No one was ever brought to justice for Hypatia's brutal torture and death, but Cyril the Archbishop was later canonised by the church as a saint. And so 1100 years later, Renaissance artist Raphael, commanded by a bishop to remove Hypatia from his great School of Athens fresco, committed a wonderful act of bold deception. He moved her from the centre to the left, between Pythagoras and Parmenides, he lightened her skin to be many shades more pale than a Greco-Alexandrian woman’s skin would have been, and he disguised her features to resemble that of the ruling Pope’s most beloved nephew. Thus Hypatia was resurrected in art and stands among history’s most exceptional minds in Raphael’s timeless work. When I study her in this extraordinary work of art my heart always sets a little to aching. All the other philosophers are busy studying their works, discussing matters of great importance and buzzing with the energy of instructing some of their students. But Hypatia stands alone in her white martyr’s robes, side-on with her solitary gaze on us, the spectators. Her beautiful eyes silently, but assuredly, entreat us not to forget - as history almost did - that she too deserves to be in this venerable gathering of philosophy's greatest men. If you enjoyed this article, please buy my book "Western Values Defended: A Primer"

15 Comments

|

Reality Check Radio: Six Hit Shows in One Week on the Assassination Attempt on Trump. NZ is Engaged!

Post Archives

July 2024

Links to Other Blogs |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed