This website uses marketing and tracking technologies. Opting out of this will opt you out of all cookies, except for those needed to run the website. Note that some products may not work as well without tracking cookies.

Opt Out of Cookies|

By Olivia Pierson

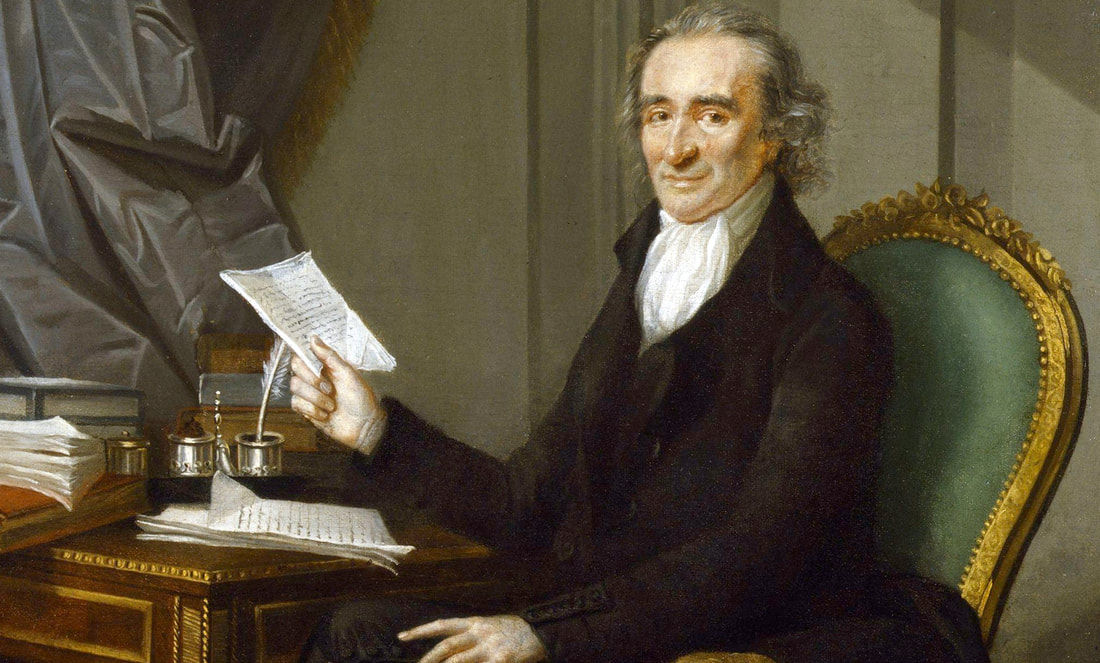

[First published on Insight @ The BFD 22/8/19] If ever there was a man who could be deemed worthy of remembrance for his radical commitments to the cause of human freedom, Thomas Paine would be that man. Born to a Quaker family of Thetford, England, in 1737, Paine played a crucial part in the American Revolution of 1776 and the French Revolution of 1789, after his popular pamphlets Common Sense and The American Crisis swept through the Western worlds, both new and old, placing before the public eye in simple, yet dramatic terms, the virtues of self-government and individual liberty. He despised tyranny and oppression, the divine right of kings, organised religion, the death penalty and slavery. He loved reason, freedom, the emancipation of mankind and was the first person to coin the term “the United States of America” and to use the term “democracy” as something other than a pejorative. Paine thought the revolution in America did not go far enough since it did not abolish black slavery and he thought the revolution in France went too far since it became entrenched in medieval violence and bloodshed. He took bold private stands in both revolutions against his own friends, colleagues and comrades, never willing to compromise his conscience, but always ready to go it alone if that’s where the courage of his convictions took him – and it nearly always did. Paine had been introduced to Benjamin Franklin in London, who wrote him a letter of recommendation precipitating Paine’s immigration to Philadelphia in 1774, whereupon he found employment editing a new publication, the Pennsylvania Magazine. Under an array of pseudonyms, Paine began to write articles attacking slavery as well as abuses enacted by the British monarchy upon the colonies of America. The American Revolution As Americans began to think and only whisper about throwing off the British yoke after the battles of Lexington and Concord, in 1776 Paine roared it from the proverbial rooftops when he anonymously penned Common Sense, seriously laying out the case for the independence of the thirteen American colonies and a complete break with England. This powerfully treasonous pamphlet caused an overnight sensation as it was read aloud in ale-houses, public squares, churches and meeting-houses up-and-down the East Coast: “Even the distance at which the Almighty hath placed England and America, is a strong and natural proof, that the authority of the one, over the other, was never the design of Heaven. The time likewise at which the continent was discovered, adds weight to the argument, and the manner in which it was peopled increases the force of it. The reformation was preceded by the discovery of America, as if the Almighty graciously meant to open a sanctuary to the persecuted in future years, when home should afford neither friendship nor safety.” THOMAS PAINE, COMMON SENSE, 1776 Paine’s timely but scorching plain-speak inspired the revolutionary mind of Thomas Jefferson and other Founding Fathers of the Continental Congress to write the Declaration of Independence and send it to the parliament of King George III. War with England became inevitable. By the end of ’76, Paine found himself aide-de-camp to George Washington’s top military commander, General Nathanael Greene. America’s citizen militias were being thoroughly routed by superbly trained British armies. Morale bottomed-out and Americans were deserting the Continental army in droves. Paine, wanting to cement their fighting spirit, penned the American Crisis and Washington had it read aloud to all of his troops on Christmas Day. It opened with these words: “These are the times that try men’s souls. The summer soldier and the sunshine patriot will, in this crisis, shrink from the service of their country; but he that stands it now, deserves the love and thanks of man and woman. Tyranny, like hell, is not easily conquered; yet we have this consolation with us, that the harder the conflict, the more glorious the triumph.” THOMAS PAINE, THE AMERICAN CRISIS, 1776 After the War of Independence was resoundingly won, President Washington once remarked, “Americans owe their liberty to Thomas Paine, more than any other man.” But years later, when Paine desperately needed his friends in America to come to his aid while he suffered on death row in a French prison (Luxembourg), only one saw fit to really help him. The French Revolution 1789 saw the outbreak of the Revolution in France, which Paine, who was once again back in England building a prototype for a bridge, supported wholeheartedly in principle. In order to refute Edmond Burke’s sulphurous and counterrevolutionary diatribe, Reflections on the Revolution in France, in 1791 Paine penned the great document, The Rights of Man, forever linking the cause of mankind with the cause of natural rights. Revolutionary France lapped it up gratefully, but the work’s anti-monarchy sentiments made him an outlaw in England. Paine bolted to Calais for his life. The French made him an honorary citizen and Paine was elected to the French National Assembly, where its highest committee was to decide on the fate of King Louis XVI and his queen, Marie Antoinette. Through a french interpreter, Paine made an impassioned speech to spare their lives, and though he supported the new French Republic, he advocated for both monarchs to be exiled to the United States, rather than be executed, not only on the basis that Paine felt a natural abhorrence for the death penalty but also because King Louis had come to America’s defence by sending troops to help fight its war of independence against Britain: “It is to France alone, I know, that the United States of America owe that support which enabled them to shake off an unjust and tyrannical yoke. The ardor and zeal which she displayed to provide both men and money were the natural consequences of a thirst for liberty. But as the nation at that time, restrained by the shackles of her own Government, could only act by means of a monarchical organ, this organ, whatever in other respects the object might be, certainly performed a good, a great action.” THOMAS PAINE, SPEECH TO THE FRENCH ASSEMBLY, 1792 His defence of the king and queen marked Paine out as an enemy of the Montagnards, the revolutionary group in power who instigated the Reign of Terror, led by Jean-Paul Marat and Maximilien Robespierre. By the end of ’93, Paine was arrested and imprisoned without trial for being an enemy British citizen. During his ten months in prison, where rogue fevers, typhus and a weeping open wound on his stomach severely and permanently damaged his health, where every day he expected to lose his head as those all around him were losing theirs (sometimes over a hundred heads in one night), Paine became deeply embittered with thoughts that President George Washington et al had betrayed him by not securing his release on the basis that he was an American citizen; he was one of America’s most famously celebrated revolutionaries. But this is also where he managed to write a draft of his famous work on Deism, The Age of Reason. Aside from railing against the wedlock of church and state, it was Paine’s attempt to rescue a benevolent, yet non-interventionist, God from religion – a religion which he saw as violent, spurious and corrupt. Intended for a French audience, but dedicated to his fellow “Citizens of the United States of America,” he opened Part One of the book with these words: “I believe in one God, and no more; and I hope for happiness beyond this life. I believe in the equality of man; and I believe that religious duties consist in doing justice, loving mercy, and endeavouring to make our fellow-creatures happy. But, lest it should be supposed that I believe many other things in addition to these, I shall, in the progress of this work, declare the things I do not believe, and my reasons for not believing them. I do not believe in the creed professed by the Jewish Church, by the Roman Church, by the Greek Church, by the Turkish Church, by the Protestant Church, nor by any church that I know of. My own mind is my own church. All national institutions of churches, whether Jewish, Christian or Turkish, appear to me no other than human inventions, set up to terrify and enslave mankind, and monopolize power and profit. I do not mean by this declaration to condemn those who believe otherwise; they have the same right to their belief as I have to mine. But it is necessary to the happiness of man that he be mentally faithful to himself. Infidelity does not consist in believing, or in disbelieving; it consists in professing to believe what he does not believe.” THOMAS PAINE, THE AGE OF REASON, 1794 The Age of Reason became one of the most controversial books of its time, and for subsequent decades hastened many a publisher and bookseller into the bonds of prison-time for trucking in outright blasphemy. On a personal note for Paine, the book served to sever almost all of his friendships in the United States. He was regarded as a “profligate atheist.” By dint of a freak mistake, the executioners failed to see the ominous chalk-mark scrawled on Paine’s prison door when they came to take the next batch of men and women to the guillotine – and so he was spared that night. (Paine thought it was because of his deathly fever that he couldn’t be moved.) Three days later, Robespierre was executed by guillotine and the Reign of Terror came to an end. It was future American president, James Monroe, then Ambassador to France, who finally came through for Paine by securing his release from prison. Monroe made Paine a guest in his Parisian home while he convalesced, and it was there that Paine finished The Age of Reason. Still galled by the pangs of perceived betrayal by his American fellow-revolutionaries, from Paris Paine embarked on a scathing public letter to his former friend and hero, President George Washington. The letter caused an uproar in America, as the Federalists and Democratic Republicans battled out their differences: “The part I acted in the American Revolution is well known; I shall not here repeat it. I know also that had it not been for the aid received from France, in men, money and ships, that your cold and unmilitary conduct (as I shall show in the course of this letter) would in all probability have lost America; at least she would not have been the independent nation she now is. You slept away your time in the field, till the finances of the country were completely exhausted, and you have but little share in the glory of the final event. It is time, Sir, to speak the undisguised language of historical truth.” THOMAS PAINE TO GEORGE WASHINGTON, 1796 In this same letter, Paine also takes pains to vehemently fulminate against the character of future president, John Adams: “John Adams has said (and John it is known was always a speller after places and offices, and never thought his little services were highly enough paid) John has said, that as Mr. Washington had no child, the Presidency should be made hereditary in the family of Lund Washington. John might then have counted upon some sinecure himself, and a provision for his descendants…John Adams is one of those men who never contemplated the origin of government, or comprehended anything of first principles. If he had, he might have seen that the right to set up and establish hereditary government never did, and never can, exist in any generation at any time whatever; that it is of the nature of treason; because it is an attempt to take away the rights of all the minors living at that time, and of all succeeding generations.” THOMAS PAINE TO GEORGE WASHINGTON, 1796 When Thomas Jefferson won the U.S presidency over John Adams’ second term in 1801, Jefferson officially invited Paine to return home to America, which Paine did immediately. Although Jefferson had been warned by everybody not to associate with Paine, that “atheistic drunk” with the twisted mind, Jefferson walked with him arm-in-arm about the public square as an open and public show of their friendship. Despite the heavy censorship of Paine’s work The Age of Reason, millions of people on both sides of the Atlantic read the humane and Deistic reasoning of its texts, and the late 18th Century epoch itself began to be referred to as “the Age of Reason.” John Adams vociferated bitterly and sarcastically about this swing of grand fate, but even he came to admit that: “I know not whether any man in the world has had more influence on its inhabitants or affairs for the last thirty years than Tom Paine […] Call it then ‘the Age of Paine.’” JOHN ADAMS TO BENJAMIN WATERHOUSE, 1805 On a tragically pathetic note, toward the end of his life, Paine, who was then scarred by poverty, loneliness and chronically broken health (and probably alcoholism), went to vote in a local election but was turned away and scolded that he was “not an American citizen,” so dishevelled and raw was his appearance to his fellow man. Paine died on the 8th June 1809. Six people came to his funeral, two of whom were black freedmen. The Quakers refused his last will and testament to be buried in their graveyard, so he was buried on his own land in New Rochelle, which the Continental Congress had gifted him straight after the Revolutionary War when they once felt that they were in his eternal debt. Over a century later, the 19th Century American writer and orator, Robert G Ingersoll, who lived in a time which, because of its intellectual freedom, he thought he owed to the thinking of Paine, wrote these words about him: We must also remember that there is a difference between independence and liberty. Millions have fought for independence — to throw off some foreign yoke — and yet were at heart the enemies of true liberty. A man in jail, sighing to be free, may be said to be in favour of liberty, but not from principle; but a man who, being free, risks or gives his life to free the enslaved, is a true soldier of liberty. Thomas Paine had passed the legendary limit of life. One by one most of his old friends and acquaintances had deserted him. Maligned on every side, execrated, shunned and abhorred — his virtues denounced as vices — his services forgotten — his character blackened, he preserved the poise and balance of his soul. He was a victim of the people, but his convictions remained unshaken. He was still a soldier in the army of freedom, and still tried to enlighten and civilize those who were impatiently waiting for his death. Even those who loved their enemies hated him, their friend — the friend of the whole world — with all their hearts. On the 8th of June, 1809, death came — Death, almost his only friend. At his funeral no pomp, no pageantry, no civic procession, no military display. In a carriage, a woman and her son who had lived on the bounty of the dead — on horseback, a Quaker, the humanity of whose heart dominated the creed of his head — and, following on foot, two negroes, filled with gratitude — constituted the funeral cortege of Thomas Paine. He who had received the gratitude of many millions, the thanks of generals and statesmen — he who had been the friend and companion of the wisest and best — he who had taught a people to be free, and whose words had inspired armies and enlightened nations, was thus given back to Nature, the mother of us all. ROBERT G INGERSOLL, THOMAS PAINE, 1870 And on that salutary note, ladies and gentleman, I leave you to ponder the unusual life of Thomas Paine, a tragic hero if ever there was one; writer, revolutionary, philanthropist and advocate for free thought and human liberty. If you enjoyed this article, please buy my book "Western Values Defended: A Primer"

10 Comments

Michael Stone

28/8/2019 09:13:04 am

A great overview of a great man.

Reply

28/8/2019 03:19:48 pm

Thank you for a fine article. May I share it? And please check out my work on my website and at this link: https://vimeo.com/146810610

Reply

Olivia

28/8/2019 03:45:13 pm

Yes... You can share it. Thanks.

Reply

Olivia

28/8/2019 09:09:34 pm

Another most interesting fact about Paine, that I should’ve included in this piece, was his influence on Jefferson regarding the Louisiana Purchase. After his release from prison in the Luxembourg, Paine had been invited by Napoleon Bonaparte to dinner in Paris where Bonaparte picked his brains about all matters on his foe, England.

Reply

Kerry Deane

28/8/2019 10:19:41 pm

Excellent article,Olivia. Enjoyed it immensely. When we think about men like Paine,we can only be saddened by the extent to which Western civilisation has departed from the lofty ideals espoused by them;even if not in a literal guise then certainly in spirit. I think we are in need of a renaissance in enlightened thought. This is clearly apparent from the fact that in the 21stcentury these great 19th century men retain a current lustre. In fact one can go back even further to John Milton the 17th century English philosopher, who in 1644 issued this injunction:”Though all the winds of doctrine were let loose to play upon the earth,so truth be in the field,we do injuriously by licensing and prohibiting to doubt her strength. Let her and falsehood grapple;whoever knew the truth put to the wire in a free and open encounter”Thise who seek to stifle free speech would do well to afford due weight to this sentiment.

Reply

Olivia

29/8/2019 10:57:38 pm

Great quote from Milton!

Michael

30/8/2019 08:30:17 pm

Olivia...You are a precious treasure all the more valuable in comparison to those who represent Objectivism. The Paine article is great journalism about a man who was fundamental to America. I want to send you a bouquet of emotional flowers for the great work you do.

Reply

Olivia

31/8/2019 01:41:43 am

Why, thanks!

Reply

Michael

2/9/2019 09:12:27 pm

Olivia...I watched the video that Parille posted of Amy Peikoff and if I didn't know who she was, I never would have guessed she had any relationship to Ayn Rand. She appeared to be an airhead snowflake with a wicked prejudice against being feminine. You. on the other hand, are a shining example of intelligence, talent and efficacious behavior. Thanks for being you.

Reply

Mike Gemmell

4/9/2019 07:28:36 am

Magnificent, Olivia! My feelings range from extreme sadness to extreme rage when I think of how his life ended. I can only hope that the original Thomas Paine and the modern-day versions of him (one of whom, Petr Beckmann, I was fortunate enough to hear speak) understand during their lifetimes that the life of a hero is often not an easy one and that one day his/her labors will be celebrated and admired as they so richly deserve.

Reply

Leave a Reply. |

Reality Check Radio: Six Hit Shows in One Week on the Assassination Attempt on Trump. NZ is Engaged!

Post Archives

July 2024

Links to Other Blogs |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed